Over the last year, I’ve evolved a production Flutter + Firebase app from a handful of packages into a single monorepo that supports web, mobile, shared business logic, CI/CD, and multiple environments. This post explains the structure I landed on, why I rejected several “clean” architectures along the way, and what actually holds up once the repo crosses a few hundred thousand lines.

A well-organized repo lets you ship faster, onboard teammates more easily, and reason about complex app behavior confidently.

Here’s how we got there.

Why most Flutter repo advice breaks down past MVP

In the beginning, there were two repos - app and console. Each had its own main.dart file and pubspec.yaml file so we could keep things separated and manageable. The app repo contained the mobile app code, and the console repo contained the web console code. But there was a lot of duplication starting to creep in since they shared models, some business logic, and even some UI code. At that point, shared was born.

We moved the shared models and other common code into shared and slimmed down the others. While it took some juggling and googling to get shared included properly into app and console when running locally and when deploying through CI, we got it working and it was good.

With three repos, things were nicely separated and it was making sense. We even set up separate color schemes in vscode for each repo so we knew which we were editing. That was nice, but got confusing on holidays when all three repos became Halloween orange and black…

MVP was released and we started getting feedback from users. We were happy to see that the web console and iOS and Android apps were working and that users were finding them useful. But with three repos, we had to manage duplicate secrets for integrations, each update required two or three git commits, and tooling such as fastlane and CI had to span repos – cross-repo coordination was a pain.

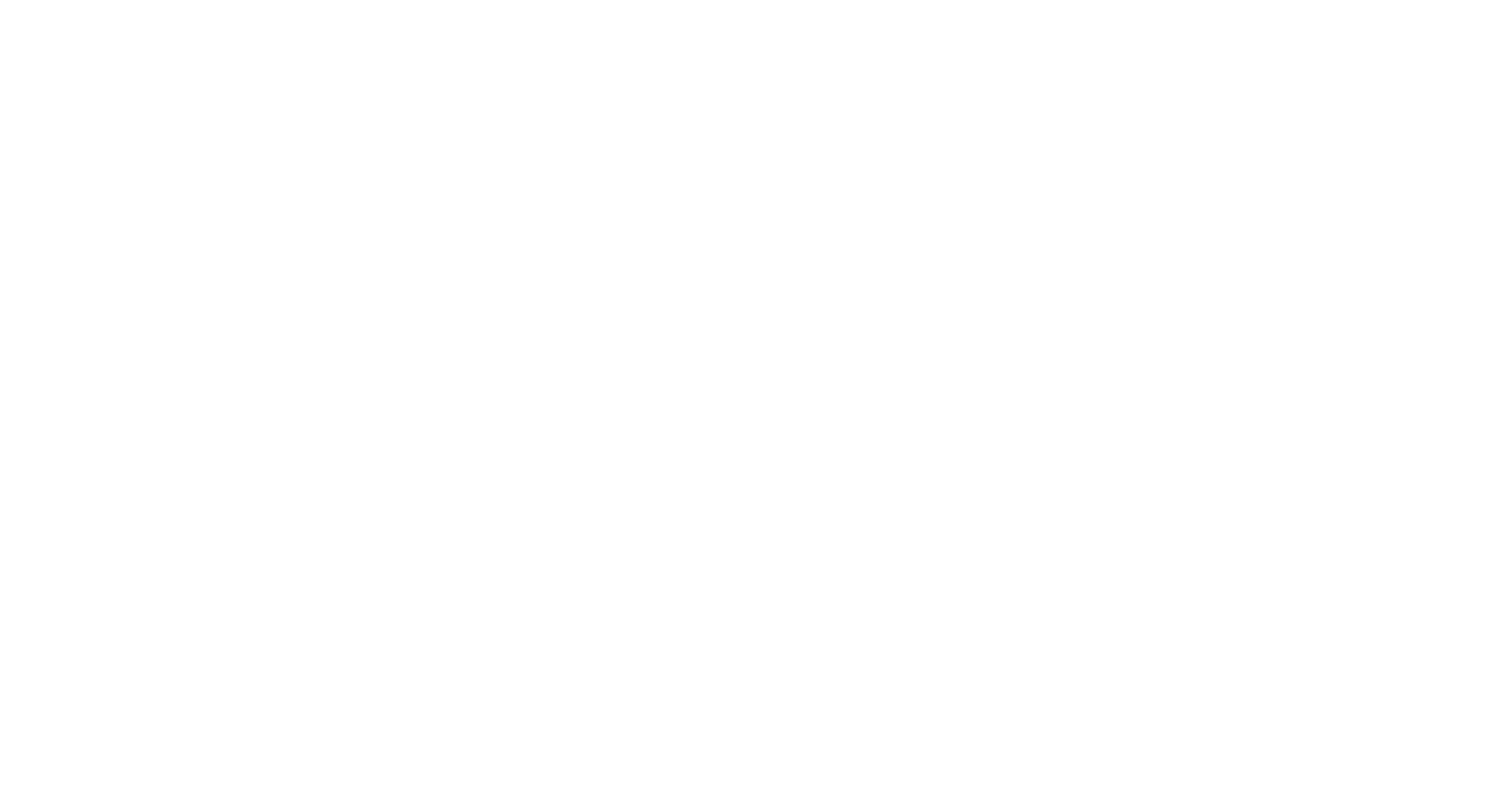

One repo, multiple entrypoints (web console + mobile app)

Ok, so one repo to rule them all, right? We decided to merge the three repos into one mono-repo. We kept the projects and their dependencies separate to minimize the impact of merging. We set up multiple workspaces in vscode - probably incorrectly - it was pretty hard to find good documentation on that process. We were able to get it working and we were down to one git repo for all three projects.

It was easier to manage the file structure and deployments, and we were able to work on all three workspaces within one IDE environment. It was also nice that moving files or code to shared didn’t require multiple git commits.

After some months and many pubspec.yaml updates later, we noticed that we were spending a lot of time syncing dependency versions between the three repos. When we updated a dependency used by both app and shared, two pubspec.yaml files needed to be updated, requiring a fair bit of futzing with version management. Even more so when all three pubspec files needed to be updated. It was nice keeping dependencies separate between app and console, but the trade-off was starting to get cumbersome.

An actual comment in both the app and console pubspec.yaml files:

# Keep these in sync with our shared library’s pubspec.yaml - don’t use “any” here

Side note – any is a topic for another post. Suffice it to say, we avoided it and used the actual version number for dependencies.

One day, we bit the bullet and merged all three workspaces/projects into one.

The real win - the mono-project

Well, I don’t think we invented the mono-project (er, project), but we did find a way to simplify our workflow and eliminate some of the pain points we were experiencing. The day we deleted the last of the extra pubspec.yaml files, we felt like we had finally found the sweet spot. With tree shaking, we got over our concern about including unused dependencies in app or console and we were able to share one pubspec.yaml file between all three sections of the project.

Ok, it took some more juggling and created an opportunity. We have a main.dart for app and another for console. They are the entry points and are responsible for setting up firebase and other dependencies, environment detection, and handing it off to the router. They are pretty similar and it was tempting to merge them. Instead, we abstracted all startup logic out into a runFirebaseApp() call and pass in dependencies as needed.

ls -l the project directory:

├── .vscode

│ ├── launch.json

│ └── ...

├── android

├── assets

├── ios

├── lib

│ ├── app

│ │ ├── main.dart

│ │ └── ...

│ ├── console

│ │ ├── main.dart

│ │ └── ...

│ └── shared

├── pubspec.yaml

├── scripts/src

│ ├── functions

│ ├── tools

│ └── shared

│ └── ...

├── README.md

├── ...

Here are the main() functions for both app and console.

lib/console/main.dart

Future<void> main() async {

await runFirebaseApp(

() => AppSettings(singleInstanceLoginRoles: {}),

() => FirebaseInfo.console(firestoreLoggingEnabled: false),

getProviderContainerOverrides: () async => [

payrollRegistryProvider.overrideWithValue([csvPayrollAdapter, quickbooksPayrollAdapter]),

],

child: Main(),

);

}

lib/app/main.dart

Future<void> main() async {

await runFirebaseApp(

() => AppSettings(singleInstanceLoginRoles: {.guard, .supervisor}),

() => FirebaseInfo.mobile(firestoreLoggingEnabled: false, enableMobileCrashReporting: true),

getProviderContainerOverrides: () async {

final isSimulator = Platform.isAndroid ?

!(await DeviceInfoPlugin().androidInfo).isPhysicalDevice :

!(await DeviceInfoPlugin().iosInfo).isPhysicalDevice;

return [isSimulatorProvider.overrideWithValue(isSimulator)];

},

beforeRun: () async => await SystemChrome.setPreferredOrientations([DeviceOrientation.portraitUp]),

child: Main(),

);

}

To make this work, we added configurations to launch.json for console and app, specifying where main is. We have staging and production flavors set up as well as the ability to run against individual local Firebase emulators. We’ll dive deeper into flavors and emulators in another post.

.vscode/launch.json “configurations” element

{

"name": "CONSOLE staging-local",

"request": "launch",

"type": "dart",

"flutterMode": "debug",

"program": "lib/console/main.dart",

"preLaunchTask": "Generate Staging Messaging Service Worker",

"args": [

"--web-port",

"4000",

"-d",

"chrome",

"--dart-define",

"FIELDIO_PROFILE=staging-local"

]

}

Shared vs app-specific code: what must be shared

That’s how it shook out. It’s easier to maintain and we spend less time futzing with dependencies, git, and vscode workspaces.

With that in place, let’s back up and discuss what is actually really helpful to have in shared that has worked well for us.

This app has two main targets - a web console and a pair of mobile apps. The console is used by managers and office staff and the app is used by field personnel. Broadly, the field personnel populate the database, and the office staff consumes. Of course there is a lot more interaction, but that captures the broad strokes.

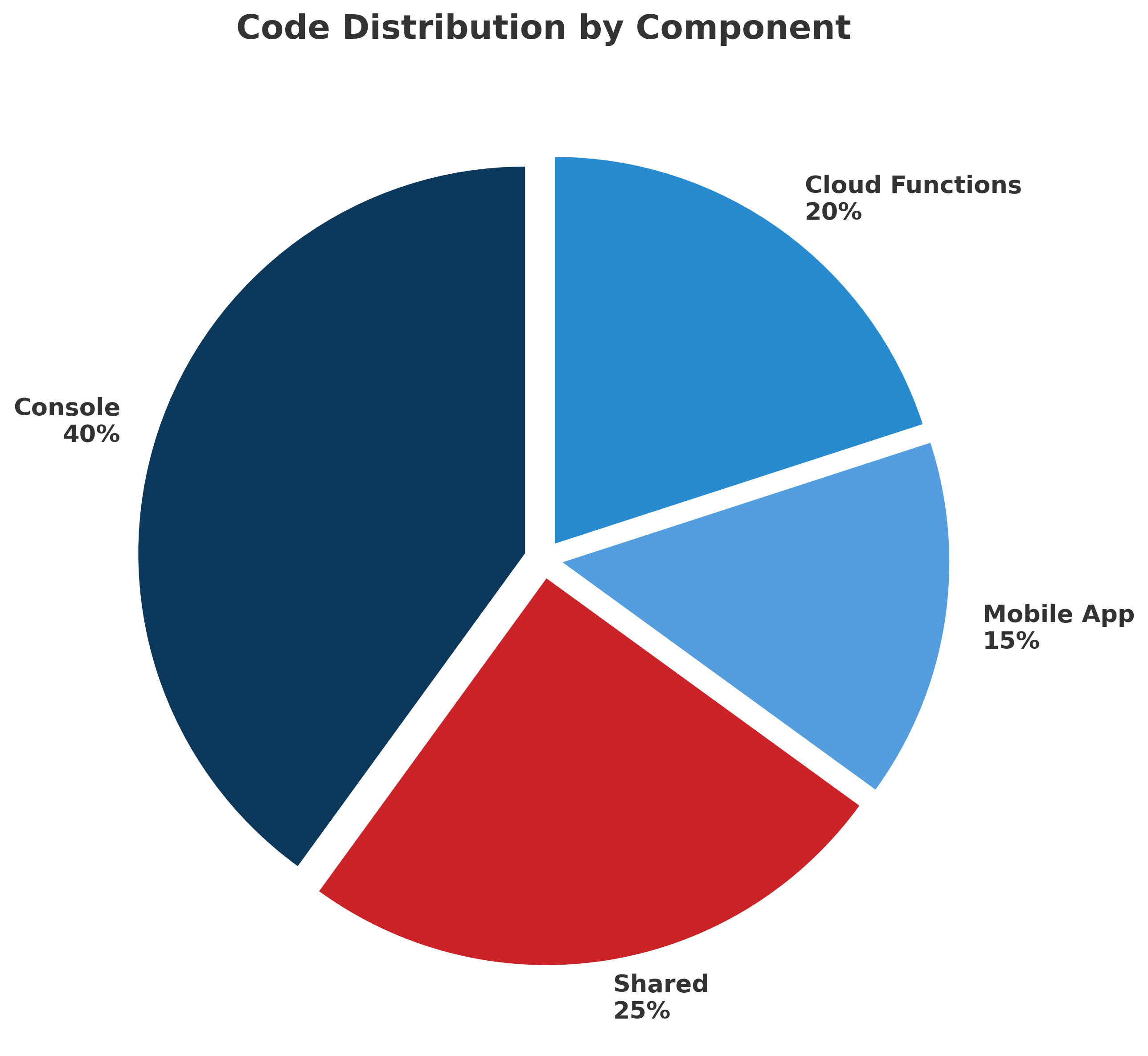

Code breakdown

Just over 40% of the code lives in the console. That tracks with reality: admin tools, reporting, configuration, and edge-case handling tend to concentrate complexity. This is where flexibility and UX nuance cost real code. This isn’t arbitrary — it reflects where real complexity lives in a multi-target app.

About 25% sits in shared. That’s the core—models, business rules, validation, and cross-platform utilities. This is the leverage layer. Every line here reduces duplication and keeps the two targets evolving together instead of drifting apart.

Another 15% is the mobile app. The app is focused on workflows, offline behavior, and device-specific UI, while leaning heavily on shared logic and backend guarantees.

The remaining 20% is in Cloud Functions. This layer enforces business rules and handles third-party integrations. Stuff like credential management, payment processing, report generation, AI workflows, notifications, and other backend services. Actually, a lot of cool stuff happens here.

Shared code - what’s in there?

Shared isn’t just a junk drawer — it’s the foundation we reuse, extend, and safeguard. The shared layer is dominated by three things: models, state orchestration, and reusable UI.

models form the backbone, defining the domain in a way both the console and mobile apps can rely on. To improve our developer experience, we built a code generator that leverages dart_mappable and riverpod (optional) to generate type-safe multi-tenant Firestore CRUD operations and Riverpod providers. This greatly simplifies access and provides type-safe and reactive access to the database. Stay tuned for a blog post about that - we called it firestore_crudable.

Close behind are providers, which centralize state, coordination, and cross-cutting behavior. This uses Riverpod and includes providers for various managers, services, and other shared state.

Most of the remaining shared code are views that encode higher-level UI patterns used in multiple places. We use the same views for the various authentication flows on mobile and console. Because the UX flow for auth is a bit involved, it was worth it to make them responsive and reusable.

Beyond that core, shared becomes a collection of enabling infrastructure: common types, launch and bootstrap logic, theming, dialogs, authorization, payments, deep linking, storage, and small utilities like helpers, extensions, and decorators. Individually these pieces are modest, but together they keep business rules consistent, reduce duplication, and allow both targets to stay focused on their specific workflows rather than re-solving the same problems.

If it’s referenced by more than one target and truly generic, it belongs in shared.

What I’d do differently if starting today

I like where we ended up. It was a result of living with early decisions that worked well until they didn’t. If I were starting a multi-tenant, multi-target Flutter app today, I’d start with this end in mind.

I would start with a single repo with multiple targets. I would have one pubspec.yaml and a separate main.dart for each target. I would use a shared code base for models, providers, and some views. I would strongly consider having all models in shared, even if a few are only used by one target or the other. Most will be shared.

I would identify a clean and type-safe pattern for interfacing with the database. When we started the project, we hit Firestore directly - lots of “stringly-typed” code (using strings where types should be used). We moved to freezed, then to dart_mappable with our home-grown “firestore_crudable” library that we turned into a code generator. The important thing here is to have a clean and type-safe pattern for interfacing with the database. Keep those details away from the UI code.

Just saying

The opinions expressed here are my own. I’m not saying you should do it this way or that way. I’m saying what has worked for us and what I would do differently if starting today. This comes from real-world experience shipping and maintaining Flutter apps in production, with real users and real constraints.

If you’re wrestling with repo structure in your Flutter app, try mapping your own line counts and see where the real complexity lives — you might be surprised. Please feel free to reach out with any questions or comments. I’m always happy to hear from you.